CUBA – Richard Velarde once spent hours with a wire hanger in hand, slowly scraping away the calcium deposits in his water heater. It’s a common water problem for the Village of Cuba, where Velarde is serving his second stint as mayor.

“Sometimes you open your faucet and nothing will come out because the buildup is so bad,” he said. “The little sprayer hoses on the side of the sink – you can’t use those here. You better have filters if you want to save your water heaters and washing machines.”

Now the rural community has a potential solution for its water woes – one that could also help other cities and towns in New Mexico improve their water quality.

The water department’s wells and tanks date to the 1960s, meaning the town of fewer than 800 people in Sandoval County is constantly repairing and replacing valves and pipes.

“It seems like all I deal with is infrastructure here,” Velarde said. “Repairs are so expensive. It’s hard enough for small towns to pay the bills sometimes, so that doesn’t leave a lot for things like engineering estimates.”

When a company approached Velarde with an offer to build a facility and treat water pumped from the brackish aquifer beneath the village, he jumped at the opportunity.

Cuba signed a memorandum of understanding in May with the KNeW Co. to build a plant that would pump and treat water from the aquifer, providing at least 450,000 gallons of water a day to the village.

But the salty water is laden with calcium, sodium and sulfates. Big cities such as El Paso and San Diego treat brackish groundwater with desalination. That’s not an option for rural Cuba, with its four-person water department.

“Desalination is expensive,” said Aubrey Howard, co-founder and CEO of the KNeW Co. “Little villages can’t afford reverse osmosis plants and the energy requirements that come along with that.”

Desalination also produces large amounts of brine.

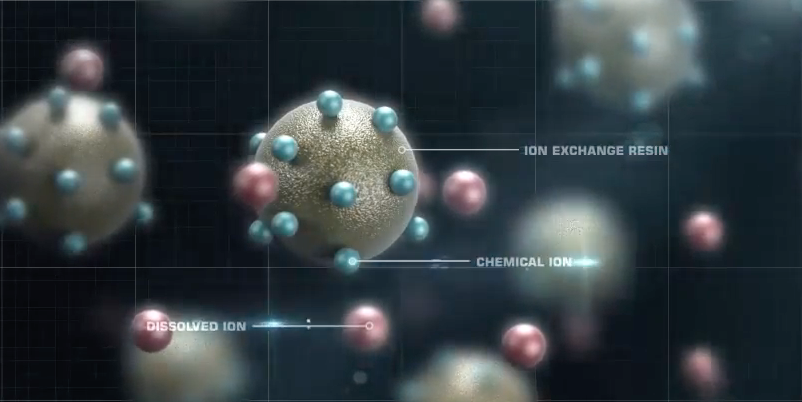

Instead, the plant will use KNeW Co.’s ion exchange technology pioneered by John Bewsey, a South African chemical engineer and technical director at Trailblazer Technologies. KNeW stands for “potassium nitrate ex waste.”

Water tanks are filled with small resin beads act that like little magnets, pulling out the sodium, calcium or magnesium in brackish groundwater or mine wastewater.

One set of tanks removes all the positively charged ions, which attach themselves to the beads.

Negatively charged beads in another tank remove chlorides and sulfates.

“You’re left with water which is neutral and has nothing dissolved in it,” Bewsey said. “The trick that we came across is to convert all those unwanted ions – which in the past nobody knew what to do with – we convert them into fertilizer. In particular, the one that is valuable is potassium nitrate. That pays for all the trouble that you’ve gone to take those dissolved solids out of the water.”

The fertilizer side of the plant means the company turns a profit even without selling the treated water. This allows KNeW to provide clean water to Cuba, free of charge.

Cuba and KNeW Co. may apply for grants with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and New Mexico to help finance the plant. The company would like the facility to be in production by the end of 2021.

After the $10 million water treatment plant is built, Cuba would own and operate the facility. The company would manage the “waste” at the adjacent fertilizer plant.

Bewsey uses his technology to treat acid mine drainage and brackish groundwater at a pilot plant in Johannesburg.

The plant has tested the ion exchange method on water with the same makeup as the Rio Puerco aquifer.

The process “worked beautifully,” Bewsey said, and it cleans the water so thoroughly that some minerals will have to be added back in to meet drinking water standards.

The Cuba project is the first attempt by the California-based company to expand the use of Bewsey’s technology into North America.

A New Mexico State University professor and water scientist serves as a technical adviser for the company, which first began looking at the Rio Puerco aquifer several years ago.

The Cuba project builds on a 2011 study of the aquifer commissioned by Sandoval County.

Levi Casaus Jr., an operator with the Cuba water department, said the new infrastructure and a cleaner water supply could help break the costly repair-and-replace cycle for municipal lines and home appliances.

“We have hard water even after filtration,” Casaus said. “You’ll see the calcium buildup in your sink, shower head and water heaters. We also get blockages in our meters and municipal lines. It costs a lot of money to repair and replace those, and it also means we’re wasting water.”

The Cuba system has two water tanks, which are on separate land from the pumping and treatment site. The older wells get less productive each year, so it is a struggle to fill both tanks and maintain good water pressure.

“We have some areas where if the tank pressure drops, they simply don’t get water,” Casaus said. “When water levels go the other way and get too high, we get leaks and full breaks in our lines. It’s a balancing act. We’re playing with the cards we’ve been dealt.”

A central plant closer to the village would address those water quantity and pressure problems.

The proposed plant would include two wells to pump 2,700 feet down into the aquifer, tapping into a much larger water source than what Cuba can currently pump 700 feet down in a separate aquifer.

St. Johns, Arizona, has also signed a memorandum of understanding with KNeW Co. to build a similar plant to convert brackish aquifer water into drinking.

Mayor Velarde said the construction, along with steady jobs at the water plant and gross receipts taxes from the fertilizer plant, could help the economy of Cuba, where the roads are lined with long-closed businesses.

“We’ve got to try something different,” Velarde said. “We’re getting by with what we have right now, but we have an opportunity for it to be better. A cleaner water supply would mean a lot for this community.”